You can see it from a distance: The “Lulatsch” or “beanpole”, a colorful-striped chimney stack towering 300 meters over the Chemnitz-Nord coal-fired power plant and glowing like a beacon in the night sky. But soon, the puffs of smoke that still hang over the chimney in this industrial city two hours south of Berlin will stop – forever. From that point on, the Lulatsch will be a reminder that a new era of energy has begun.

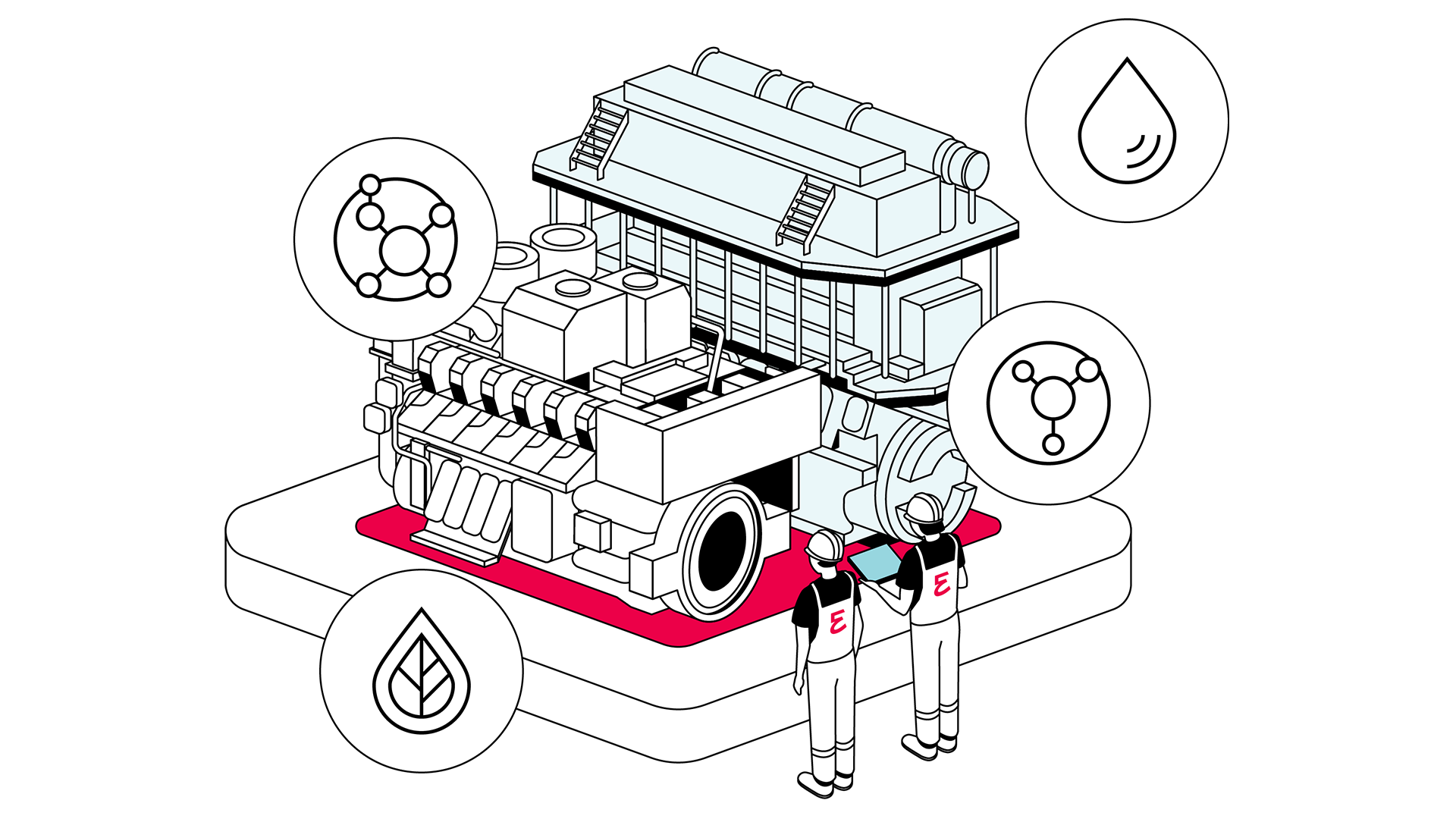

Thanks to the project “New heat for Chemnitz”, commissioned by the local energy provider eins energie in sachsen, around a quarter of a million people here will soon get most of there heat and power from two new combined heat and power (CHP) plants, powered by Everllence gas fuel engine technology. The two new plants, MHKW Chemnitz-Nord and Altchemnitz, will supply the city with 150 megawatts of electricity and over 130 megawatts of thermal output – enough heat for some 40 percent of the population. “It’s a unique solution for maximum efficieny,” says Martin Domagk, Project Manager at Everllence.

Gas engines cut carbon emissions by 60 percent

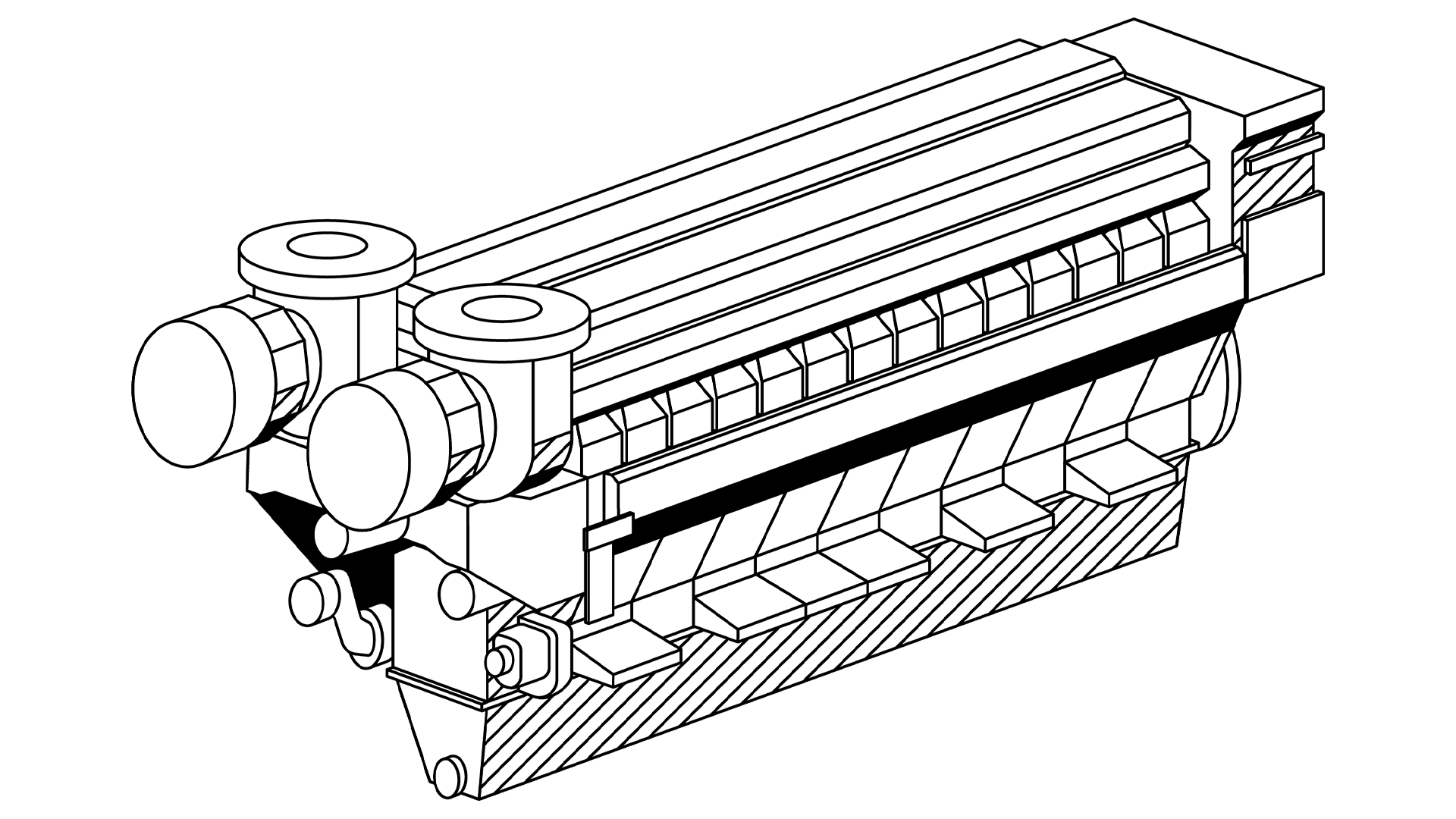

As we walk through MHKW Chemnitz-Nord, Domagk explains what makes both new plants exceptional: the dynamic and highly flexible 20V35/44G TS gas engines that power them. Here at MHKW Chemnitz-Nord seven such engines have been installed at the heart of seven separate machine halls, and another five at Altchemnitz.

“The engines can go from idle to full load in minutes,” says Domagk, “and each can produce nearly as much thermal as electrical energy.” Moreover, the engines make an effective use of their fuel, operating a total efficiency of up to 90 percent. “It’s an ideal solution for cogeneration plants.”

“The engines can go from idle to full load in minutes.”

Martin Domagk, Project Manager, Everllence

How to choose power for a CHP

“For us, the quality of the engines and how they suit our Chemnitz-specific needs were the key factors,” says eins energie Project Manager Tino Schlemmer in his office on the old grounds. From the windows, you can hear the constant waterfall-like sound of the cooling tower of the old plant, but that too will stop in January 2024.

“The task was to find a solution that was environmentally sustainable, cost effective and offered a very high security of supply,” says Schlemmer. He and his team visited other similar CHP construction sites with Everllence or comparable engines at their core. “The visits convinced us of the engines’ efficiency, but also allowed to see what we wanted to do differently.” For example, eins energie chose to put each engine into a single machine hall, making it possible to repair an engine without affecting the operation of the others.

Why CHPs need flexibility in the energy transition

eins energie has set itself the goal to become a climate-neutral energy supplier by 2045 – with a focus on hydrogen, since Chemnitz is set to become one of the four hydrogen hubs in Germany. And the Everllence engines are helping to set the path: The engines are a bridge technology, able to run now with an admixture of up to 25 percent hydrogen and Everllence is already developing new engines and retrofit packages to run 100% on hydrogen. Plus, they are able to run with increasing shares of climate-neutral fuels such as biogas and synthetic natural gas (SNG) without modifications.

“Flexibility becomes even more important with the ongoing transition towards renewable energy, accompanied by the liberalization of the energy markets and the current political turbulences affecting the supply of some energy sources,” says Schlemmer. “So, we need plants that are quick to switch on and off and to control their power outputs.”

In comparison to the old coal-fired plant, which would take hours to restart, the pre-warmed engines need less than three minutes to deliver 100 % electrical output, and only a few minutes more to produce thermal energy. “Quick startup and shutdown times allow the plant to react to sudden load variations in the grid,” says Domagk. This allows them to provide seasonal, dispatchable power generation when renewable energy isn’t available.

“The criteria for choosing gas engines as the power source for their new CHP plants was centered around cost effectiveness, sustainability, security of supply and flexibility.”

Tino Schlemmer Project Manager at eins energie in sachsen

Tailoring a CHP system for the future

Both cogeneration power plants also come with sophisticated control engineering technology, points out Domagk, which allows eins energie to easily adjust to the needs of the grid: In summer, for example, when prices for electricity are high but heat isn’t needed in significant amounts, the plant focuses on providing power – in the winter, on providing heat. “Let’s say, eins energie knows the network needs 50 megawatts of electrical power. You enter the needed amount, and the engines adapt to it. The same goes for thermal energy,” says Domagk.

While here, in the north of Chemnitz, the coal-fired plant is making room for a modern gas-fired power plant these days, eins energy is already investing in energy production like wind energy, solar energy, and has further plans to add in heat pumps and electrolyzers for the production of hydrogen. But until more green hydrogen is available, gas-fired power plants remain an important step in the energy transition. Switching from coal to gas quickly cuts emissions in the short term, and the plants enable the continued expansion of renewable energy, closing the supply gap on days when there is little or no sun and wind. “We’re convinced that gas-fired plants will play a decisive role for a long time,” says Schlemmer, “They guarantee security of supply.”

About the author

Berlin-based journalist Moritz Gathmann has been reporting as a correspondent from various regions of Europe for German publications since 2004. His work has been published in DER SPIEGEL magazine, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and other media.